Balancing Risks while Navigating the Climate Crisis

The threats and opportunities of solar radiation modification and the psychology of risk

The polycrisis poses some formidable risks. But what are risks? And how do we get a handle on them? To many “risk” is a dirty word, a forebode of disaster, and therefore it is not surprising most people are risk averse. The psychology of risk is clearly at play in the climate debate and that shouldn’t be a surprise. It is well known responses to risks are highly emotionally driven and that most people struggle to adequately analyze and assess risks.

With regard to Solar Radiation Modification (SRM) or Geoengineering many educated and wise people dismiss the enterprise altogether, referring to human hubris and its inevitable downfall. In ancient Greek mythology hubris was ultimately brought down by Nemesis, the goddess of fortune and retribution. This idea is deeply rooted in many cultures and also illustrated by the Tower of Babel parable in the Book of Genesis.

To me, the big question regarding SRM is how to assess the risks associated with deployment. It is clear that deploying SRM is not risk-free, nor is not deploying any form of SRM. The risks of SRM are highly dependent on the type of SRM. For example, if we include Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) as a SRM strategy, I am inclined to qualify it as very low risk, as CCS just cleans up some of the (fossil) carbon we have dumped in the atmosphere. Basically CCS is a way of “undoing SRM”, as the industrial carbon added to the atmosphere is also a geoengineering/SRM experiment, albeit involuntary.

At the other end of the risk spectrum, I would qualify Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) as a high risk SRM proposal, as it is relatively poorly controlled, both in space and time, and will likely cause unintended consequences in unexpected places. The “problem” with SAI is that it is economically attractive, as it could be deployed at short notice, and relatively low cost, using existing technologies. In the absence of feasible, more benign planetary cooling strategies, I expect we will see the unilateral deployment of SAI in the near future, when a country is confronted with persistent, widespread, and life-threatening extreme warming.

A SRM proposal, I believe might offer a more controlled and therefore benign strategy to cool the planet, is Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB). Brighter clouds increase the albedo of the planet, which means that a larger fraction of the incoming solar radiation is reflected back into space, a bit like a reflective sun shade for a car windshield.

In theory, MCB can be achieved by spraying fine droplets of seawater from offshore structures. While the droplets add some humidity to the atmosphere, and cause some cooling when they evaporate, it is the salt doing the trick. When the droplets evaporate the salt in the seawater crystalizes and floats in the atmosphere as an aerosol. These aerosols are expected to function as condensation nuclei for the formation of white clouds. The brightening effect was clearly shown in “ship tracks”, in particular before the 2020 International Maritime Organization ban on sulfur in shipping fuels.

The public debate about SRM is highly charged and divisive, due to the high stakes, and for reasons related to the aforementioned human hubris and the precautionary principle. A cautious attitude with regard to SRM is wise in my opinion. At the same however, I think we should be equally cautious about (involuntary) anthropogenic warming. To have a meaningful discussion about SRM we will need to properly assess the risks in my opinion.

We know there are significant risks associated with global warming and the associated extreme heatwaves and extreme storms. The risks are potentially so big, that, in the worst case, human civilization may collapse in a mass extinction event, and, in the best case, there is large consensus, mitigation and damages will cost trillions of USD in the coming decades. In other words, not doing SRM is by no means risk-free.

The risks of global warming have been widely studied, while the risks of SRM are still largely unknown. This means we are currently not in a position to make a proper integrated risk assessment. To me it appears there is an urgent need to assess the risks of SRM, without any commitment to future deployment. In fact, I believe, the sooner we assess the risks associated with different SRM proposals, the more likely it is we will choose to shelf some of the ideas brought to the table. Reversely, if we don’t do the research, we might end up in a desperate situation, and deploy SRM without properly knowing the risks. In that case we would learn the hard way about the associated risks, and potentially cause more harm than good.

When we talk about impacts of global warming and global cooling we are dealing with multidimensional risks. From the discussions I have participated in at workshops and on social media, I know SRM deeply stirs people. Some feel insulted that some humans have the arrogance to play for God and intend to improve on His work. Others are struck with fear about the potential inequality of cooling deployment, and the seemingly impossible task of fair governance (see e.g. Biermann et al.: Solar geoengineering: The case for an international non-use agreement). And again others are dumbfounded that you would not try to actively cool, when you know dangerous heating is upon us.

I have no answers as to how we may reach any form of consensus regarding de research and development of SRM. It appears to me that a discussions about risks would be helpful. I also believe we should be aware of the psychology of risk. As I am not a specialist on the psychology of risk, I will present some key concepts based on a presentation from University of Oregon professor Paul Slovic (delivered at the U.S . Nuclear Regulatory Commission 2021 Regulatory Information Conference). The key points of the psychology of risk according to Paul are (I will use italics when citing Paul’s work):

• Risk and risk assessment are subjective and value laden

• Every hazard has unique qualities that drive perceptions and behavior

• Perceptions have impacts (ripple effects, stigma)

• Trust is critical: hard won, easily lost

• Most risk perception is determined by fast intuitive feelings (e.g., dread) based on experiential thinking, rather than by careful deliberation

Without going in detail, I think these observations will be recognizable to many. For example, with regard to SRM, I observe natural scientists and engineers are much more receptive than social scientists and scholars of the humanities, which I ascribe to the different world views of these social and professional groups. This difference, between natural science and humanities, is the topic of two previous posts I wrote: The climate is indifferent about our social affiliations and our feelings and Reality blindness and possibility blindness.

Paul also asserts that trust is key when communicating about risks. Mille Bojer from Reos Partners explains in a post on LinkedIn that value-based differences can prove hard to overcome:

While INTEREST-based conflicts can generally be solved through information, compensation, or negotiation, in VALUES-based conflicts:

👉 Information is seen as PROPAGANDA

👉 Compensation is seen as BRIBERY

👉 Negotiation is seen as BETRAYAL

This I recognize as well. When there is no trust-base, based on shared values, I have experienced, that whatever argument I offer on a matter, climate change for example, it just doesn’t land. Quite often people told me the arguments I offered, including the references to scientific publications, were propaganda. And I also often sense people are not willing to reconsider their positions, as that would constitute a betrayal of their social group.

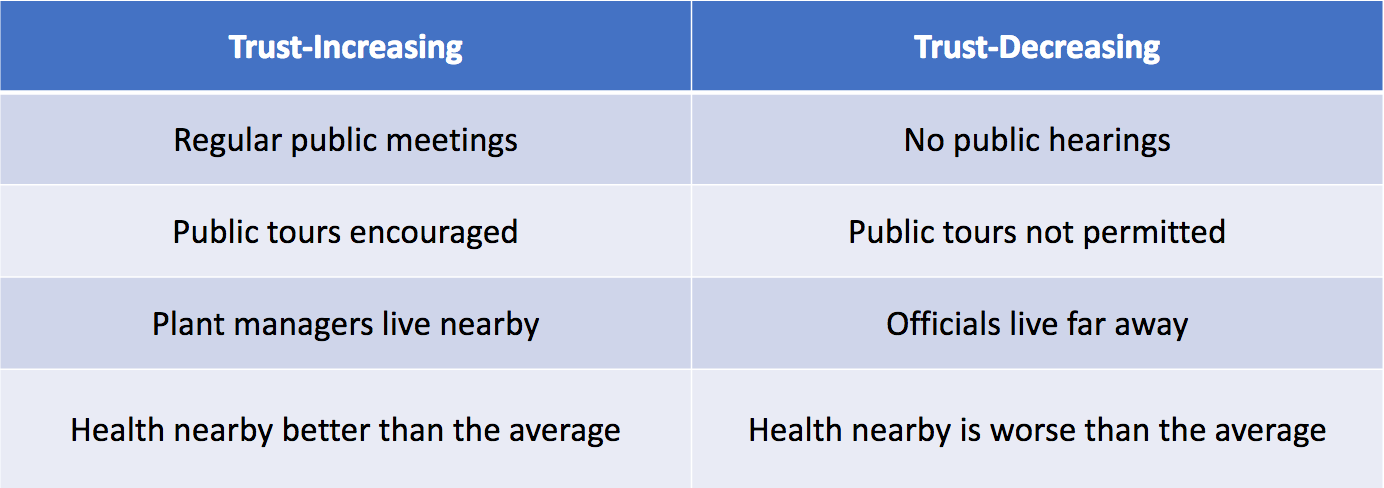

Another issue with trust is the so-called Asymmetry Principle: trust is much easier destroyed than built. The table below, with trust-increasing and trust-decreasing events, is also from Paul’s presentation.

Paul also points out there is a differential impact of news reports: bad news has a higher impact than good news.

In summary, I would argue:

we need to intentionally build trust before we can have a fruitful public discussion about SRM, and

we need to do the research, computer modeling, and field trials, before we can have a meaningful discussion about the risks associated with different SRM proposals.

I would like to end this post with a final quote from Paul’s presentation and a poll asking you how you think we should proceed with regard to SRM.

People’s political ideologies and worldviews strongly influence their perception and acceptance of risk.

Please take a moment to share your attitude toward SRM by clicking on one of the three options below:

Thank you for reading my post and supporting my work. Please feel free to leave a comment or send me a personal message.

Tycho