The climate is indifferent about our social affiliations and our feelings

The perception of CTBO at the World Energy Congress and the Amsterdam Complexity School on Climate Change

Last week I participated in the Amsterdam Complexity School on Climate Change (ACSCC) hosted by the University of Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Study. The week before I attended the World Energy Congress - Redesigning Energy for People and Planet in Rotterdam, hosted by the World Energy Council. These two rewarding experiences reminded me society is socially compartmentalized, even among the highly educated.

For example, it’s easy imagining business leaders chatting away during a round of golf. It’s also easy imagining leaders from the environmental movements catching up at an Extinction Rebellion (XR) event for example. Imaging a environmental leaders playing golf with business leaders is hard to imagine. And so is seeing corporate leaders at an XR event. And the reason is simple. It doesn’t happen.

So what, one might wonder. After four days at the World Energy Congress and the first day at the ACSCC workshop I realized this is a big deal. After all, we are in a poly-crisis because of anthropogenic drivers, forcing deep systemic changes to the energy system, the economic system and the food system. Intelligent people across the board agree these changes will be much more painful when they happen involuntarily rather than by design. Yet, the same people, with similar understanding of the human overshoot problem are not able to have constructive conversation outside of their social peer group.

I believe deep and rapid change can be achieved through legislation. For example, consider the ban on CFCs, or the ban on free plastic bags, or any other environmental protection law. These laws change the rules of engagement between humans and the environment on all levels of society.

As some of you will know I endorse a carbon takeback obligation (CTBO), which is essentially a ban on fossil carbon emissions. Last week, at the World Energy Congress, I asked many people what they thought about CTBO. Surprisingly, to me, many people working in the gas and oil industry, including CEOs, are not categorically against the proposal and show willingness the accept the extended producer responsibility. Of course they will try to water it down and negotiate the best possible conditions for their business, but there was no direct rejection when I brought it up. I believe the industry also knows something must change.

Last week, at the ACSCC workshop, to my surprise, no one showed real interest in CTBO. I pitched CTBO as a project to work on at the workshop but found no one interested. What’s going on? A room full of intellectuals, many environmental activists, all of them concerned about the climate, and no one shows interest in atmospheric protection legislation?

My take on this is that many intellectuals and activists are so distrustful, angry and resentful with the fossil fuel industry that they want to the sector wiped off the face of the earth. I understand the sentiment. For decades the fossil fuel has been lying and intentionally misinforming the public in successful attempts to frustrate effective climate policy. This malicious campaign has been influential avoiding early policy making since the early nineties, when climate change made it to the international political agenda.

Unbelievably, to this day the fossil fuel industry continue their strategy of sowing doubt and confusion. For example, for the court case of Milieudefensie / Friends of the Earth Netherlands against Shell, Shell created a foundation Milieu en Mens (Environment and Human) together with the climate skeptics from Clintel, a group known to spread lies and half truths about the climate (I wrote several posts about Clintel on LinkedIn).

The purpose of Milieu and Mens was to plea on Shell’s side and bring forward arguments that effectively question the broadly accepted science of climate change. Shell needed the foundation because they didn’t want to be seen making these claims themselves. In fact, Shell officially agrees with Milieudefensie on the science. The schizophrenia of Shell, using two disagreeing personas in court, was reported about by Dutch newspaper Trouw on April 6th. Obviously, this tactic by Shell raises moral and legal questions. For some reason I don’t understand I cannot find a link to the article online so I’ll share the picture below.

Clearly and understandably many activists hold a grudge against oil and gas. But are oil and gas the problem? Well, yes and no, I’d say. In a way fossil fuels are at the root of the overshoot problem. Industrialization was enabled by the discovery of cheap and abundant, energy-dense fossil fuels. This is in turn enabled a population explosion, a pollution explosion and an assault on biodiversity. However, it is clear these consequences were unintentional side effects of fossil fuel use.

Until at least the late sixties, early seventies, I’d argue there was no real understanding of the potential climate impacts of fossil fuel use. Around that time Big Oil did some studies regarding climate impacts which unequivocally showed that dangerous climate change was possible and likely with continued fossil fuel use. Unfortunately the industry exploited these findings to fight climate policy, rather than inform the public and propose solutions (Shell did release a video about climate impacts in the early nineties but failed to act consistently with the message of the video).

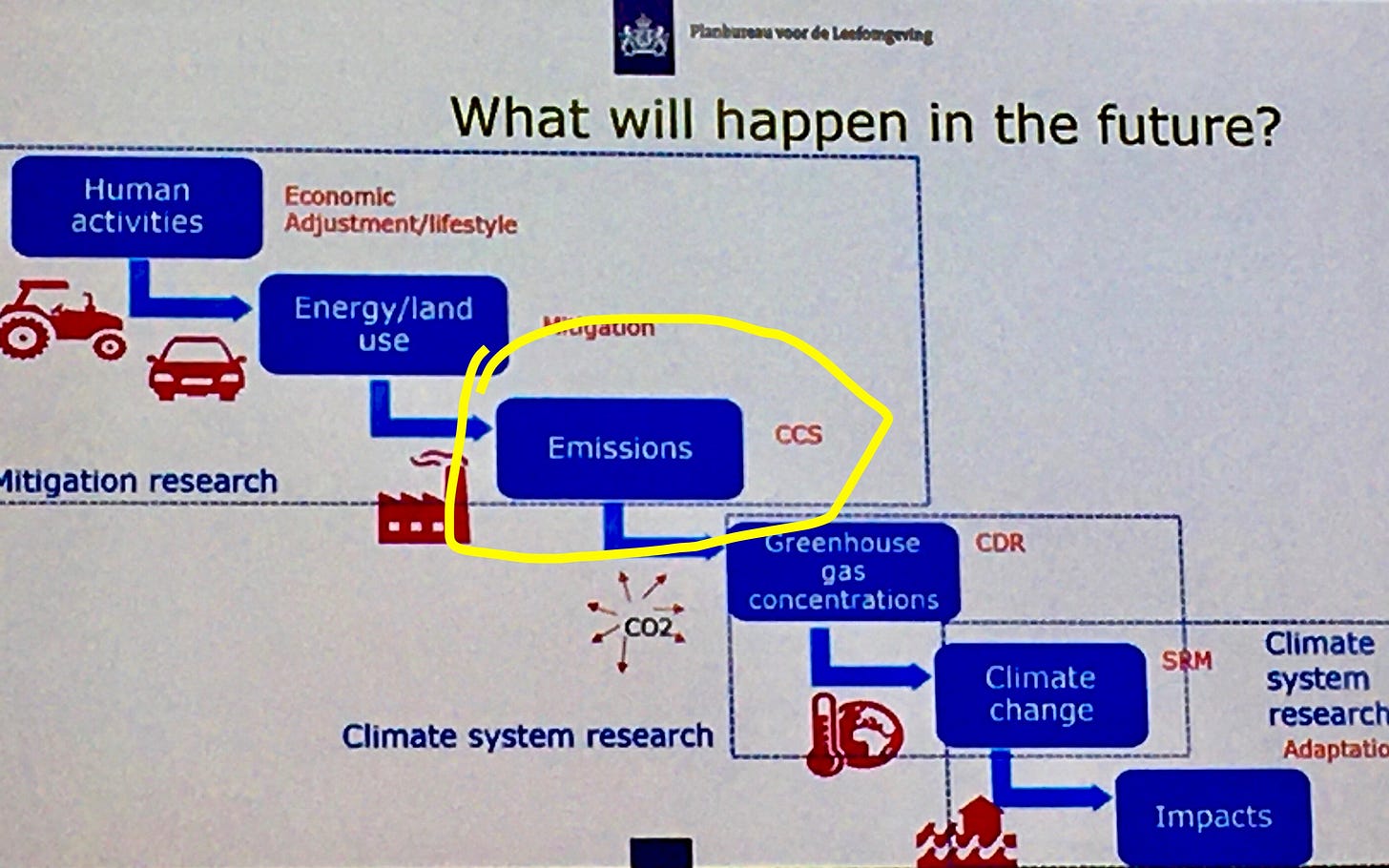

The above picture from Detlef van Vuuren’s presentation at the ACSCC workshop gives a nice overview of the anthropogenic drivers of climate change. Global warming is primarily driven by emissions from land and energy use. The text in red are suggested actions to reduce the impacts. Here I would like to draw attention to CCS (carbon capture and storage) next to the “emissions” box and SRM (solar radiation modification), next to the “climate change” box.

I draw attention to these technologies because they are passionately discredited by most environmental NGOs. Regarding SRM there is even a call for a global ban on all research and investments in the technology. While I agree a technology such as stratospheric aerosol injection is better avoided I do recognize that other more localized and controlled forms of SRM may be helpful in avoiding irreversible climate tipping points, deadly heatwaves and crop failures.

While I hope we can still avoid large scale deployment of SRM, it is clear to me, and the IPCC, that any credible pathway to netzero by 2050 includes CCS. For reasons I attribute to emotionality rather than rationality most environmental NGOs vehemently oppose CCS. They prefer a rapid, complete phase out of fossil fuels and fear CCS will delay the energy transition. I have a few issues with this position.

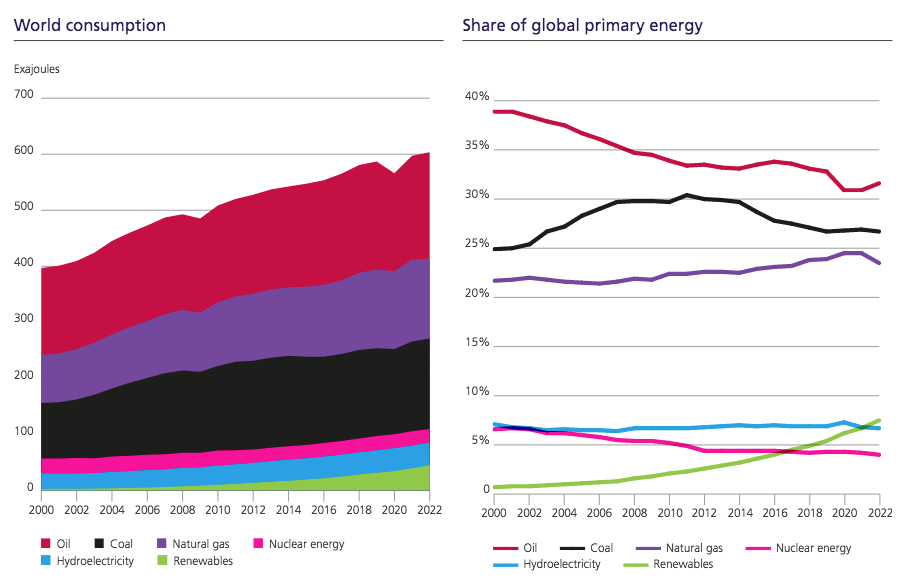

Firstly it gives me the impression they don’t realize how heavily the world still depends on fossil fuels and much time it will take to decarbonize. As the figure below shows about 80% of global primary energy consumption is still from fossil resources. While the percentage of renewables is growing remarkably, in particular in the electrified economy, the absolute total amount of fossil fuel consumption is still growing. While electrification is far from complete we will at some point have to deal with hard to decarbonize sectors such as shipping, aviation, and steel production.

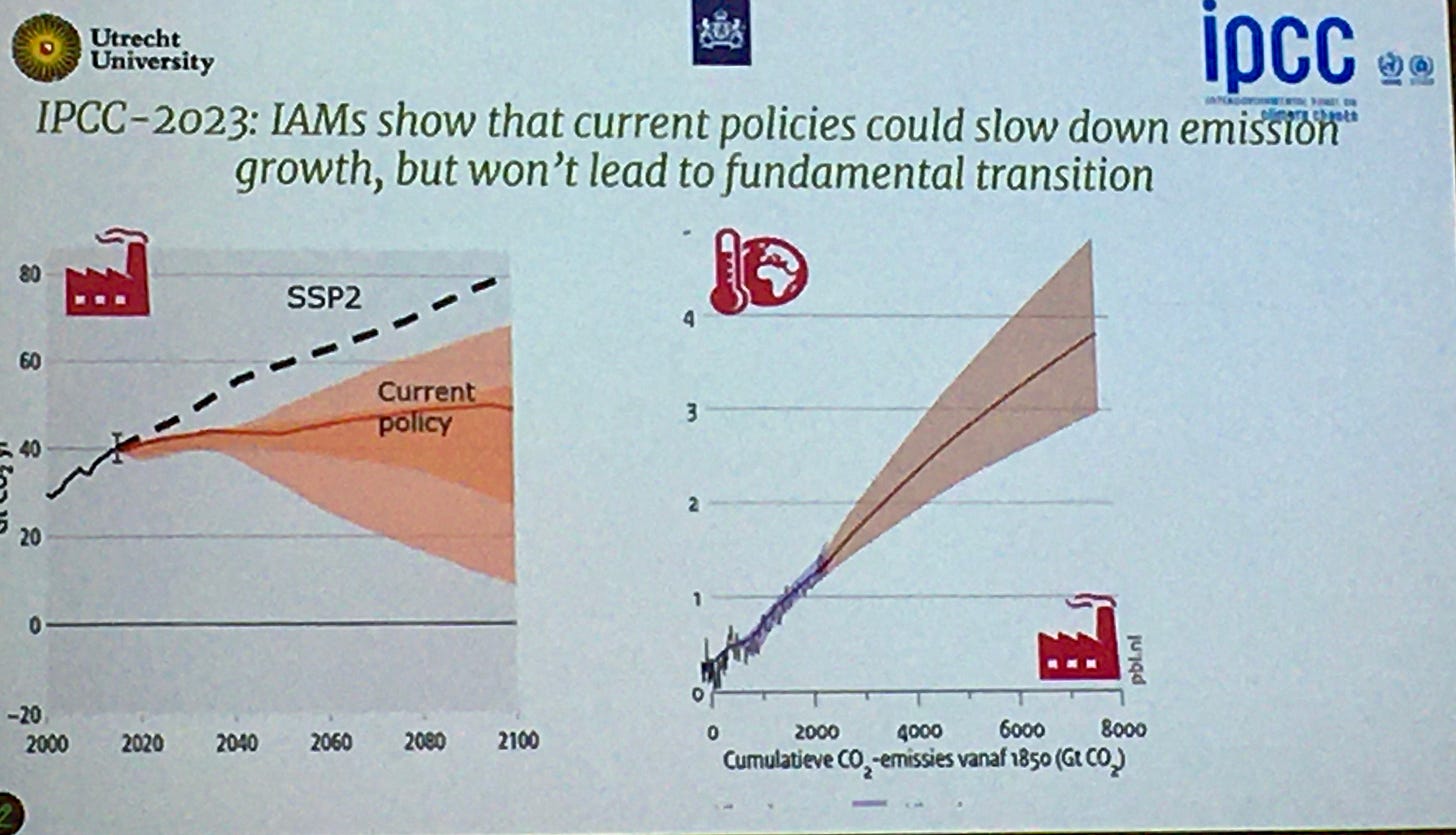

My second point, draws from the first, and presents the question, if we’re not going to use CCS, how on earth will we reach netzero on time? The total global CO2 emissions are about 40 Gton per year (and still growing) and the IPCC estimates we have a carbon budget of around 250 Gton left, if we want to stay within the 1.5 C global warming goal, as defined at the 2015 COP in Paris (estimate from Detlef van Vuuren’s presentation). That’s 6 years of current emissions, or 12 more years of fossil fuel use, if we were to linearly decrease emissions from the current level to zero starting today. None of the current policies is getting us anywhere close to this requirement, as the below slide from Detlef’s presentation shows.

From the above we must conclude the 1.5 C Paris goal is unfortunately already out of reach. This means we have to prepare for disruptive impacts from global warming over the next decades, and for this reason I think we should not rule out SRM. To me it makes sense to at least investigate our options and assess the risks. Clearly, there will be a point at which the risks of not deploying SRM will be larger than the risks associated with SRM. Having said this, I think we should avoid stratospheric aerosol injection, despite it being cost effective, as it poses a moral dilemma, because severe consequences might be felt at large distances, making any form of fair governance practically impossible.

Back to CO2, the main driver of the climate crisis. Given the large global dependency on fossil fuels I advocate the development of policy that focuses on emissions, rather than the fuels themselves. I think it is about time the fossil fuel industry is held responsible for so called scope 3 emissions: the emissions added to the atmosphere by consumers, such as people driving a petrol car. It is clear that many consumer are not in a position to curb their emissions, for example because they don’t have access to adequate public transportation and no means to buy an electric vehicle (for now ignoring the fact that current EV production is very carbon intensive; that much of the electricity in the world is still grey at best; and that electric grids worldwide do not have sufficient capacity for full electrification; and that the required critical minerals will likely become very expensive and more difficult to mine).

What if we told the fossil fuel industry emissions must stop and scope 3 emissions are their problem. We don’t want more fossil CO2 in the atmosphere and will start fining them if their product continues to cause emissions. There is a policy proposal that aims to implement this. It is called the carbon takeback obligation (CTBO) I already mentioned before. This policy extends the responsibility of oil and gas producers to the full lifecycle of the carbon molecules they sell, from cradle to grave. Since the discovery of fossils fuels we have been freely dumping the waste (CO2) in the atmosphere. The European ETS is attaching a cost to emissions, but personally I believe that is not enough. Nor do I think netzero is enough.

I agree with climate professor Myles Allen that we need geological netzero: whatever carbon we take out of the ground must go back underground, safely in the geological formations we took it from. Apart from the susceptibility of fraud and scamming with carbon credits, I believe the nature-based approach will aggravate the land-use issues we are already facing. Rather than large plantations I am a proponent of rewilding, which is largely carbon neutral and thus of minor importance on the road to netzero.

After all the natural carbon cycle consists of sinks and sources. In fact, if we include agriculture in the natural carbon cycle it would be a major achievement if we reach netzero by 2050 from land-use. Unfortunately, most proposals for large-scale sequestration of CO2 using photosynthesis have serious repercussions for the existing ecosystems and may put more pressure on biodiversity. Therefore, in my opinion, it is much safer to store excess fossil carbon into the geosphere, rather than the biosphere.

The way I see it, a desirable feature of CTBO is that it may incentivize the fossil fuel industry to convert the fuel stocks into emission free energy products, such as electric and hydrogen, and use point-source CCS to capture the carbon and inject it back into geological formations. In fact, I would make current CTBO proposals more strict and mandate geological netzero, rather than hope for the industry make this choice. It simply makes sense: whatever you take out of the ground you must put back. Obviously, CTBO cannot be introduced at full force overnight. In the beginning the takeback obligation applies to a small percentage of the carbon, say 10%, and it will be ramped up in a predefined way to reach 100% takeback by 2050.

Despite increasing social pressures the fossil fuel industry is currently still offering an economically healthy proposition to investors as there is still a souring global demand. What we are seeing is that the industry is betting on selling all its proven assets while still developing new fields. At some point, when stocks run low, or global demand starts to decrease, the industry will switch over to non-fossil energy, but currently it is in their interest to wait it out and see how the energy transition pans out. When it makes sense economically they will probably buy up some successful new energy companies and make a rapid transition away from fossil. This however will be too late from a climate science perspective.

Recalling that we have basically used up the carbon budget to stay within “safe global warming” we need to radically decarbonize and for this enormous endeavor the world would benefit from having the fossil fuel industry on board. Currently, it is near impossible for an oil and gas CEO to radically divest from fossil fuels and invest in renewables. The boards and investors/shareholders would not take it and simply replace a CEO making such a proposition.

However, when law mandates the takeback of carbon for all players in a certain market, say the EU or OECD, then the proposition changes fundamentally. Then investing in emission-free alternative energy becomes a matter of survival and doing it well might translate into competitive advantage, potentially increasing the market share of the business.

Suppose, oil and gas companies indeed choose to convert some of their reserves into emission-free alternatives, then they would take interest in the demand for their new products. Then it would make sense for the fossil industry to invest in new emission-free consumer technologies and the required infrastructure to supply the customer.

Big, energy intensive industries, such as steel production, could continue to use fossil fuel as long as they capture all emissions and pipe it back to the fuel supplier who, under CTBO, is responsible for the safe storage of the waste CO2.

Obviously, CTBO does not reduce the need for transitioning away from fossil fuels and rapid emission reductions, nor should it replace any of the existing policies, in my opinion. CTBO can supplement ETS and a carbon tax and serve as a backstop policy to ensure we reach netzero by 2050. Not unimportantly, CTBO can leverage the industrial and financial power of the oil and gas industry and make the sector a significant contributor to the much needed energy transition.

Instead of engaging in a mortal combat with the fossil industry I propose we get them on board addressing the climate crisis. After all, we all inhabit one big rock in the the universe with a thin layer of atmosphere. Whether we currently work in academia, industry or anywhere else, our children will share a common fate based on the actions we take now. In the interest of life on earth we must move beyond grievances, build trust and work together!

Background reading:

Scientific paper about CTBO in journal Joule: “Upstream decarbonization through a carbon takeback obligation: An affordable backstop climate policy”

Love your work, Tycho. And yes, I've been following the work of the Foundation for Climate Restoration which holds to an aim of restoring atmospheric CO2 and ghgs to pre-industrial levels. While the foundation is a society group, they are in conversation with any number of experts in fields that can create atmospheric draw down. They define three primary measurables to get the job done: permanent removal of CO2 (>100years), scalability i.e solution is able to scale up to gigatones of removal; and financiability i.e the solution itself creates an economic stimulus, a profit. For example Blue Planet Systems have been making commercial synthetic limestone concrete since 2021. https://foundationforclimaterestoration.org/resources/what-is-climate-restoration/ https://www.blueplanetsystems.com/ Meanwhile we need to do massive ecosystem restoration to replenish the ecological resources of the planet for our own flourishing future and there is much science indicating the degree to which such activity would reduce global temperature and weather chaos in the short term and reduce GHG's in the long term. At the interface of atmospheric and ecosystem restorations lies the possibility of using the farming of bamboo and other quick growing and harvestable organics in the manufacture of biochar for permanent sequestration.

And all the people I have been in conversation agree that al this is based on that FF emission are reduced to as near gross zero as we can get as quickly as we can get, and the goal for 2050 is still the most rapid workable goal anyone can reckon. Of course the pressures of providing dividends to investors creates a resistance from that FF industry to move profit into alternative investment. And no-one wants to move until the other 'guy' does, which is why government policy that makes everyone move together is so important.